Relationship Between Globalization and Poverty Analysis

| ✅ Paper Type: Free Essay | ✅ Subject: Economics |

| ✅ Wordcount: 2891 words | ✅ Published: 13 Oct 2017 |

1. Introduction

According to the World Bank estimates, more than a billion people—a fifth of humanity—lives on $1.25 per day, in what the UN and the World Bank classify as extreme poverty. Apart from the very poorest, there further exists an additional billion with incomes that are barely any larger: 2.4 billion people, about a third of the world population, are subsisting on less than $2 per day. These statistics, disheartening though they are, represent a significant improvement over the experiences in the past century. For instance, in 1981, 52 percent of world population was extremely poor; in 1990, that fraction decreased to 43 percent.[1]

Poverty occupies one of the central issues in the development literature, and for a good reason. The welfare implications of lifting billions out of poverty are staggering, and it is not surprising that the matter received unprecedented attention among many economists. Although the determinants of poverty are many and its enduring existence cannot be reduced to a single cause, over the last half-century we observed that the large reduction in worldwide poverty was also accompanied by significant concurrent increases in trade liberalization and economic integration across countries (see appendix Figure 1). The World Trade Organization (WTO) estimates show that merchandise trade between countries as a share of GDP increased from 18.1 percent in 1960 to 50.6 percent in 2012. This expansion of trade openness from the mid-20th century onward was to bear witness to the advent of globalization, a phenomenon that saw nations increasingly integrate their economies through trade and effacement of constraints on labor and capital mobility. Today, 159 out of 196 nations are members of the WTO, the global governing body in charge of supervision and further liberalization of international trade.

Although few topics in economics are as controversial as globalization, there is a remarkable dearth of empirical studies that examine its effects on global poverty. For example, Harrison (2006, p. 2) surveys the literature and finds that though there are recent efforts to investigate the indirect linkage between globalization and poverty (e.g., Winters et al. 2004, Goldberg and Pavcnik 2004, Ravallion 2004, Dollar 2001)[2], there are virtually no empirical studies that directly estimate this relationship. The research that focuses on the indirect relationship between globalization and poverty either attempts to proxy for poverty through income inequality, or use “computable general equilibrium models to disentangle the linkages between trade reform and poverty.” Though this line of inquiry can provide valuable insight into ways by which different channels of globalization affect poverty, it is crucial to look at the actual ex-post outcomes of these effects (Harrison 2006, p. 3). With the exception of Harrison (2006), no study to my knowledge has addressed this issue.

That said, the purpose of this paper is to fill this gap in the empirical literature. Using new data on globalization, I perform a ceteris paribus analysis to estimate the marginal effects of globalization on extreme poverty in a dynamic panel setting, controlling for institutional, demographic, and economic variables. This type of study is the first of its kind, and the results of the research presented herein can help shed light on the true effects of economic, political, and social global integrations. To preview my results, I find that poverty generally falls with rises in globalization, and that political globalization, characterized “by a diffusion in government policies,” and by the extent of diplomatic connectedness and integration within the world’s inter-governmental institutions, exerts most influence on the decline in poverty.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 motivates the discussion on the relationship between globalization and poverty, and revisits some stylized theoretical and empirical treatments on globalization and its effects. Section 3 presents the data and methodology. Section 4 presents the results, and section 5 concludes.

2. Motivation

Globalization is a multidimensional concept with great political charge. While many layperson supporters laud it for its beneficial effects on job creation, inequality reduction, and increases in per-capita incomes, opponents often blame it for, in fact, increases in inequality, erosion of environmental standards, higher poverty rates, and cultural homogenization (Dreher 2006, Akhter 2004). Among the economists, however, the controversy is usually less vehement. Although a multitude of studies have recognized a positive relationship between globalization and economic growth, income, and income convergence (e.g., Wolf and Young 2014, Dreher 2006, Sachs and Warner 1995), the impact on global income inequality remains a point of contention (Mills 2009). It is worth mentioning that a number of studies (Dreher, Gassebner, and Siemers 2012, Akhter 2004) confirm the existence of a positive relationship between globalization, human rights, and human development.

Much of the debate about the relationship between globalization and poverty is directly rooted in and motivated by the framework of the Heckscher-Olin trade theory, and the derivative Stolper-Samuelson (SS) (1941) theorem. Taking the globalization to mean increased openness to trade, then trade itself means that the international partners involved in a particular transaction obtain greater benefits by selling the good abroad rather than at home. The SS theorem predicts that an increase in the relative price of a good will also increase the return to the factor used more intensely in the production of that good. This finding implies that developing countries, whose economies are largely labor-intensive, would experience real wage increases for unskilled labor. In that respect, globalization can contribute toward alleviating poverty in countries where unskilled labor is the abundant resource (Harrison 2006, p. 10). However, the restrictive nature of the SS assumptions (constant returns to scale, perfect competition) have rendered these predictions somewhat controversial.

As mentioned earlier, there exists a lack of cross-country empirical studies that directly estimate the effects of globalization on poverty. The only exception are the models presented in Harrison (2006), who uses OLS to regress, in multiple specifications, the fraction of households living on less than a dollar per day, against country fixed effects, trade share, lags of trade share and per-capita income, inflation, government expenditures, currency crises, investment in GDP, and literacy rates. These models, though a valiant first attempt at providing the empirics where there previously were none, are insufficient to fully gauge the effects of globalization. Furthermore, Harrison’s models may suffer from misspecification and endogeneity issues through the omitted variable bias. For example, Harrison does not control for educational attainment or institutional quality, while there is strong reason to believe that these variables have a significant impact on poverty.

How do we measure globalization? A vast majority of existing research relies on proxying for globalization through trade openness or factor mobility and capital flows. Until recently, there was no unified metric that accounted for a more general concept of globalization. In this paper, I use the recently developed KOF globalization index (Dreher 2006), which captures not only the stylized economic characteristics of globalized societies (i.e., trade openness, capital flow restrictions, foreign direct investments), but also political and social channels of globalization.[3] The KOF index, measured on a scale from 1 to 100, adds data on personal contact between countries, data on information flows, data on cultural proximity, number of embassies in the world, and other political variables that better measure the extent to which a country is truly a part of the “global village.” Though skeptics might argue that these additions might not present a value added to the already existing proxies, it is important to realize that “[the] KOF indices attempt to gauge the networks and flows of ideas, people, capital, information, and goods across country borders” (Wolf and Young 2014, p. 9). The argument is that true effects of globalization cannot adequately be measured using only narrow concepts of trade and factor flows. Wolf and Young (2014), for instance, find that social globalization is robustly related to income convergence.

3. Data and Empirical Approach

The following empirical analysis develops two separate panel regression models to isolate the effects of globalization on poverty. The response variable is the percentage of “population living in households with consumption or income per person below the poverty line”[4], observed in the [0%, 100%] continuum. The poverty line is defined as less than $38 per month (2005 USD, PPP-adjusted), or $1.25 per day. The regressors include controls for globalization, population size, democracy level, education, income, and conflict incidence. Due to availability constraints, the panel in use is unbalanced and short, with up to 114 developing countries observed over the period 1990-2010 every three years for the total of eight temporal data points.[5] Poverty data come from the World Bank Povcal database, while data on controls are from ETH Zurich, World Bank World Development Indicators, and the Center for Systemic Peace. See appendix for a list of countries and descriptive statistics.

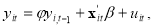

As extreme poverty is often a persistent, multigenerational phenomenon, it is plausible that past poverty will have strong predictive impact on current poverty levels, especially in developing countries with limited upward social mobility. The presence of a lagged response as an explanatory variable implies that the panel regression model is dynamic. However, once the lagged dependent variable enters the fixed-effect panel regression as an explanatory variable, regressor exogeneity does not hold. Furthermore, the lagged dependent variable causes serial correlation in the error term, potentially making the dynamic panel estimates both biased and inefficient. Therefore, the simplest dynamic panel model specification with lag of dependent variable and exogenous regressors on the right hand side could produce spurious results. With that in mind, the specification of the empirical model include two multivariate dynamic panel regression equations of the form:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

where  are the regressors,

are the regressors,

are country-specific fixed effects, and

are country-specific fixed effects, and  is the idiosyncratic error term.

is the idiosyncratic error term.

The regression methodology proceeds as follows. I estimate each equation using one-way OLS fixed effects, and Arellano-Bond (1991) estimators. The Arellano-Bond (AB) estimator applies a GMM framework to perform an IV estimation of the model parameters using lags of differenced regressors as instruments to correct for the so-called Nickell bias characteristic of dynamic panel coefficients, as well as consistency of parameter estimates.[6] The AB approach is especially designed for short panel models (many N, few T) and for models with substantial unobserved heterogeneity.

To study how globalization affects poverty through separate channels and to provide robustness, for each equation I use as explanatory variables both the aggregated KOF globalization index, and the three distinct globalization measures that proxy for the level of economic, political, and social integration. Hence, the total regression output includes eight different estimations. All globalization metrics are averaged over the three-year periods between and inclusive of the 1990-2010 window.[7] It is important to note that the above models each address different questions: equation (1) asks whether being more globalized on average affects poverty levels in developing countries, while equation (2) examines the relationship between the reductions in the fraction of poor households with respect to the variation in globalization over the observed interval.

The remaining explanatory variables include population size, log real GDP per capita (2005 USD), Polity IV democracy index, major episodes of political violence, and primary and secondary school gross rate enrollments. Along with the one-period lag of dependent variable and the three measures of globalization, the models feature eight or ten variables on the right-hand side, depending on the specification. Given prior relevant theoretical and empirical treatments in development literature, there are strong reasons to believe that the above explanatory variables have significant impact on the incidence of extreme poverty. For example, Harrison (2006, abstract) finds “evidence [to] suggest that the poor are more likely to share in the gains from globalization when there are complementary policies in place.” Furthermore, “such complementary policies include investments in human capital and infrastructure, as well as policies to promote credit and technical assistance to farmers, and policies to promote macroeconomic stability.”

The educational attainment and Polity IV data serve as a proxy for the levels of human capital and institutional quality with respect to the levels of democracy. Economists agree that institutions matter for development. For instance, in the context of globalization and international trade, Bliss and Russett (1998) and Yu (2010) show that democracies both foster trade with all nations and trade more between each other. Democratic countries therefore seem to reap greater benefits from the international trade aspect of globalization. Major episodes of political violence (MEPV) measures the incidence and intensity of politically instigated conflict within a country. An ordinal variable, it contains data on politically motivated violent conflicts that resulted in at least 500 deaths within a given year. The conflicts are coded for time and intensity, and include data on independence, interstate, ethnic, and civil wars and conflicts. Why violent conflicts may affect poverty is relatively straightforward: war breaks up families, diminishes human capital, and destroys factors of production necessary for economic growth. Apart from the usual controls for population size and relative wealth which proxy for countries’ size and relative importance in the world economy, geography, legal origin of political institutions, religion, and other relatively time-invariant properties can also have an impact on poverty levels.[8] This time-invariant, unobserved heterogeneity is captured in the country-specific fixed effects (not reported).

4. Results

Table 1 presents regression results when total globalization is included as a regressor, and Table 2 reports results using the three disaggregated globalization metrics proxying for political, social, and economic integrations.

Several results become immediately obvious. Table 1 suggests that total KOF globalization index, accounting for the integration within the economic, political, and social international networks, exhibits mostly consistent strong negative correlation with poverty levels and reductions. For a unit increase in average extent of globalization, the percentage of people living in extreme poverty falls by between 0.14 and 0.16 percentage points in both OLS and AB specifications. This result is in line with much of the existing research, which finds that globalization has beneficial impact on income level, growth, and convergence. The KOF globalization index, among other factors, increases in trade openness, FDI flows, internet usage, and decreases in trade and capital flow restrictions. Intuitively, poverty lag enter the equations in Table 1 highly significant, in accordance with the casual observation that poverty is a persistent phenomenon. The remaining variables’ marginal effects exhibit consistency in the direction on the impact on poverty level or changes, although only primary and secondary gross enrollment rates, and democracy levels, exhibit any statistical significance. Somewhat curiously, we observe that poverty levels are positively correlated with levels in democracy, a relationship that is significant in one estimated equation.

Table 2 disaggregates the KOF globalization index into three constituent categories. Curiously, economic globalization—capturing data on capital flows and trade restrictions—seems to be having adverse influence on headcount. Social globalization, which includes data on personal contact, information flows, and cultural proximity is of little statistical importance, while political globalization seems to be the most significant component of globalization driving decline in poverty levels and changes. Political globalization accounts for international treaties, number of embassies, participation in UN Security Council missions, and membership in international organizations. One possible explanation is that global political connectedness opens other venues for economic development. For example, membership in military alliances (e.g., NATO) or increased contacts and treaties with other nations around the world could correlate with increased political stability and a greater number of trade partners. The coefficients on education and conflict incidence mainly follow intuitive reasoning, although population size and per capital income remain insignificant in all eight regressions. It is possible that the statistical significance of other variables is eroded by the presence of multicollinearity.

5. Conclusion

This paper has employed new data on globalization, as well as the consistent estimation techniques in order to directly study the relationship between globalization and poverty in a dynamic panel setting. Supplementing and improving on Harrison (2006) by adding additional regressors, I estimate eight different regressions using both a composite measure of globalization as well as its three constituent measures proxying for economic, political, and social aspects of globalization. The main finding is that the average extent of globalization (especially political) is a good predictor of the decline in poverty levels and changes in poverty levels in the post-Cold War era in developing economies. A possible interpretation could be that political integration is a prerequisite for opening the doors to the flow of people, information, goods, and ideas across countries.

However, room for interpreting policy implications could be somewhat limited in scope. Certainly, few countries today remain pariahs in the international community, and advancing political integrations in terms of military alliances, treaties signed, and trade blocs has improved growth prospects in many countries (e.g., former eastern bloc). Opening political relationships with more nations and finding strategic partners in all forms of international cooperation could bring forth opportunities for greater political stability, growth, and diffusion of good governmental policies and ideas. Future research in this direction could examine a more causal link between globalization and poverty by furthering the empirical methodology to include a panel vector autoregression, and studying granger causality and impulse responses of poverty to shocks on globalization and related variables.

[1] All estimates on this found on the World Bank website.

[2] As cited in Harrison (2006, p. 2).

[3] A more detailed explanation of the KOF index can be found at URL: http://globalization.kof.ethz.ch/media/filer_public/2014/04/15/method_2014.pdf.

[4] World Bank definition.

[5] The years are 1990, 1993, 1996, 1999, 2002, 2005, 2008, and 2010. Note that due to data limitations, 2010 replaces 2011 as the last year in the dataset.

[6] See Nickell (1981) for a thorough treatment of the dynamic panel bias.

[7] So for instance, the observation in year 1996 is the average of values in 1994, 1995, and 1996.

[8] For example, Gallup et al. (1999) examine the relationship between geography and economic growth and find that location and climate significantly affect income levels and growth. La Porta et al. (1999) show that French legal origins correlate with poorer government performance in terms of economic development.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing stye below:

Related Services

View allDMCA / Removal Request

If you are the original writer of this essay and no longer wish to have your work published on UKEssays.com then please click the following link to email our support team:

Request essay removal